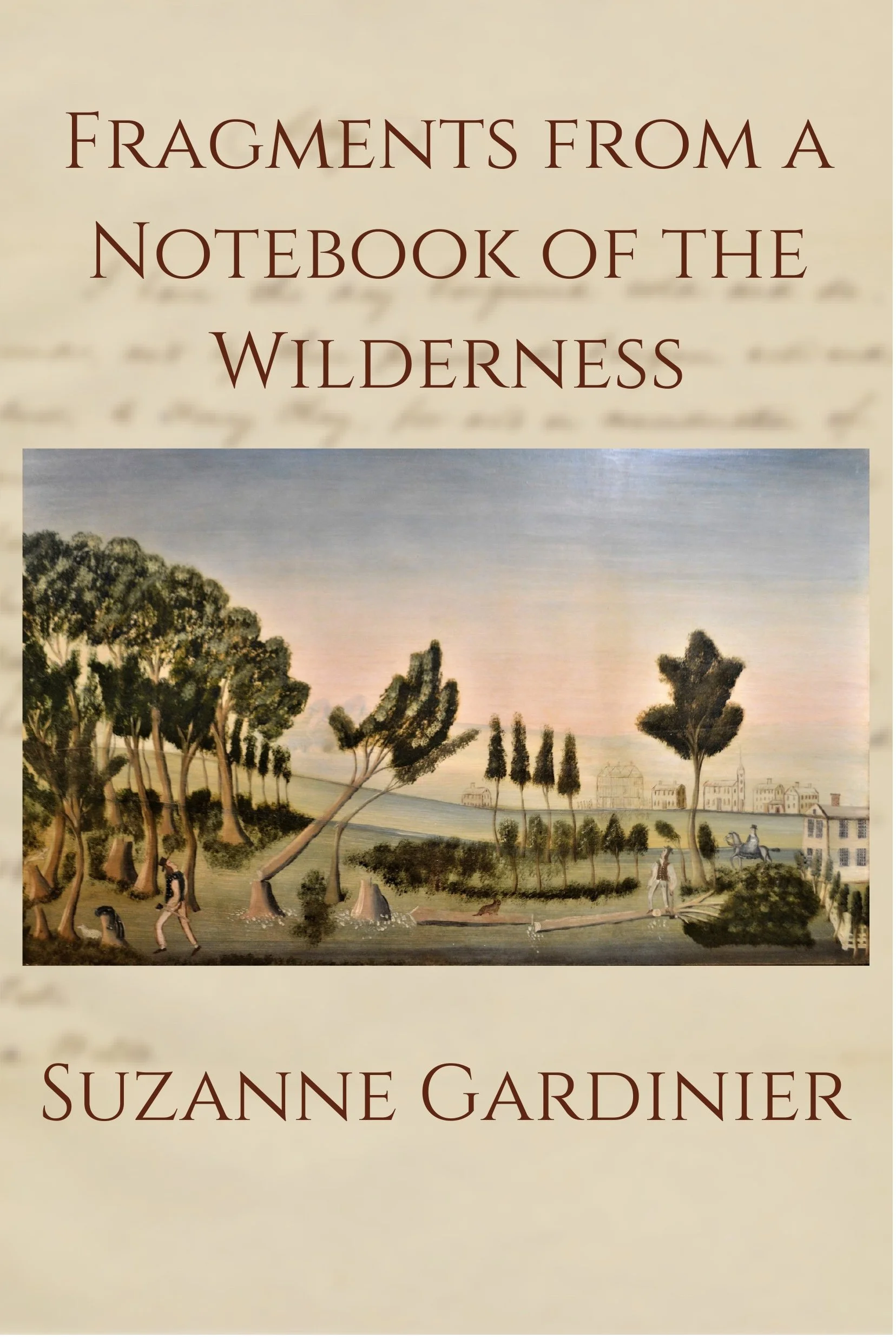

Fragments from a Notebook of the Wilderness

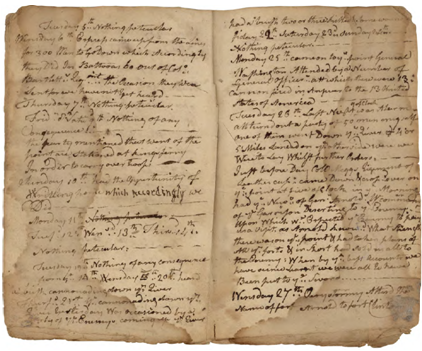

"This notebook found in pieces in a box while digging a garden

on Hudson Street. Original written by hand, ‘Wilderness’ on the cover.

Some pages illegible but this noted in what follows and all transcribed

as faithfully as possible, with gaps and other strangenesses intact.

The gardener

Fragments from a Notebook of the Wilderness

Index

Fragment 1: In Which Grant Titus Clears Henry Shaw’s Field...1

Fragment 2: In Which Rachel Titus Prepares Henry Shaw’s Boots...5

Fragment 3: In Which the Denizens of the Wilderness Are Disposed Of...6

Fragment 4: In Which Appears Henry’s Brother Hugh...7

Fragment 5: In Which Congressman Shaw Remembers His Term’s Beginning...10

Fragment 6: In Which Hugh Shaw Keeps Sheep...11

Fragment 7: In Which Congressman Shaw Remembers His Term’s End...16

Fragment 8: In Which Mrs. Shaw Prays For Her Daughter Who Is Dying...17

Fragment 9: In Which Grant Titus Has His Wish...18

Fragment 10: In Which Robert Shaw The Congressman’s Son Listens to the Ghosts of Washington and Finds His Truest Contribution To The Land Is Departure...22

Fragment 11: In Which Appears the Gardener...31

Fragment 12: In Which Appears Grant Titus’s Wife At Pinkster Time...32

Fragment 13: In Which She Is Brought To The City...33

Fragment 14: Her Dream That Night...35

Fragment 15: Her Speech During the War...36

Fragment 16: Grant Titus’s Wife’s True Name...39

Fragment 17: In Which She Passes Someone On the Road And Steps Down...40

Fragment 18: In Which White Joseph Makes The Doors...41

Fragment 19: In Which Black Joseph Is Born...45

Fragment 20: In Which Little Joseph Cuts Fenceposts For Mrs. Shaw In Chautauqua...46

Fragment 21: In Which Little Joseph And His Brothers Attend To Their Leases...47

Fragment 22: In Which Black Joseph Returns Laundry With His Mother...50

Fragment 23: In Which He Looks For His Mother Who Walks At Night...52

Fragment 24: Concerning Little Joseph’s Last Day...53

Fragment 25: Concerning the Chautauqua March Night...55

Fragment 26: Where The Girl Who Filled The Lamp Came From...56

Fragment 27: In Which Lucy Fisher And Her Son Discuss The Removal With Their Relations...57

Fragment 28: In Which Lucy Fisher Can’t Sleep...61

Fragment 29: Lucy Fisher’s Father’s True Name...64

Fragment 30: Concerning Billy Fisher’s Hair...65

Fragment 31: In Which Billy Fisher’s Grandson Joins The Army Of The Potomac...69

Fragment 32: In Which Claire’s Nephew Visits His Father In Prison While She Translates The Messages From The West...75

Fragment 33: Concerning Ely The Jackets’ Relation In The City...86

Fragment 34: Concerning Officer Meagher’s Nephew George In The Army Of The Potomac...94

Fragment 35: In Which George Meagher Joins The Army Of The Potomac...103

Fragment 36: Concerning George Meagher’s Sister’s Employment Security...104

Fragment 37: Concerning Black Joseph’s Last Day...105

Fragment 38: [Illegible]...111

Fragment 39: In Which Adam Jacket Walks In The Sky...112

Fragment 40: Concerning The Djo-Gaa-Oh And The Dam...123

Fragment 41: In Which The Gardener Looks Up...135

Fragment 42: In Which Appears Joseph’s Granddaughter Janie...136

Fragment 43: Concerning This...144

Fragment 44: In Which The Gardener Walks...159

Fragment 43: Concerning This

Originally published as "Around Midnight,"

The Paris Review, Spring-Summer 2001

Around midnight Janie heard a key in the lock while she was doing the dishes; she thought it was her son Clay come home early, or Jake forgot his umbrella, or maybe she heard wrong with the water running and it was the pigeons who scratched the sill when it rained. That you, Jake? she called. You losin already? She looked over her shoulder with soap on her hands and she laughed. Well, well. Ain’t I seen you someplace before.

Her hair was wet and the shoulders of her coat and Janie smelled roses. Maybe you did.

On the playground, right? And you forgot your sweater.

That’s right.

No, it was Miss Bracey’s, and you wouldn’t salute the flag after my mama told you about Carolina times.

May laughed. I forgot about that.

No, it was at the back of Mr. Dent’s, wasn’t it.

Mr. Dent’s been gone a long time.

In June. You had a flowered dress on, didn’t you.

You’re thinkin of a pretty girl. Somebody else.

Not somebody else, Janie said with her back turned. She’s standin in my kitchen.

Turn around. I got a flowered dress on right now. Janie clanked the last washed plate on the stack. You too busy to invite me in?

You don’t need invites. You got a key. May took off her coat and put it over the back of a chair. How’d you know it wasn’t Jake in here?

When’s the last time Jake did a dish. She stood close behind Janie. It’s Monday, she said. Jake’s playin cards with the fellas. What’s doin with you? Where’d you get those nice pajamas?

I guess you know. Some sweet mistreater. May put her arms around her and Janie turned the water on harder for the rinsing. Now she’s comin around messin up the silk, soakin wet from the rain.

I took off my coat. Nothin wet but my hair.

That ain’t what I heard.

May kissed the back of her neck. Come on, Mrs. Pink she said. Don’t be mad at me.

I got a stack of dishes here.

Smells like you’re eatin chicken while everybody else got rainwater and grass. Not even much grass.

Chicken and biscuits.

That Gallant Fox still feedin you?

Yesm.

Come on, onion girl. Her mouth was soft and she put her hands on Janie’s hips. When’s Clay comin home.

He’s gone to Lorraine’s sister’s and he brought his horn. You know how they get. Won’t be back till dawn.

All right then. Come on. Come dance with me.

Janie took a dish from the washed stack and rinsed it and put it in the drainer. You run out of kitchen boys to dance with?

I don’t want no kitchen boys.

Ain’t what I heard. She was moving her hands sweet and slow and making the silk move and Janie closed her eyes.

But you been savin yourself just for me. Ain’t that right, Mrs. Pink.

Janie sighed. Go put on a record then.

You got any refreshments?

I might. Go on.

May took her hands away and Janie listened to her go in the other room with her shoes on and take them off and walk over to the Victrola. Put on Madame R, she called over the water. She ain’t afraid to tell you how bad you are. But she didn’t. Janie rinsed the last dish and wiped her hands on a cloth and took in two wet glasses and a bottle of gin; May was standing at the window in her stockings lighting a cigarette, Standin in the rain and ain’t a drop fell on me, a voice like a thunderstorm in the middle of the night and the cornet trading bars with her and the left piano hand climbing up behind, Standin in the rain and ain’t a drop fell on me. May was wearing a flowered dress but a different one and she put her arms around Janie’s neck, and Janie put out her hands to dance the way she would with a stranger. My clothes is all wet but my flesh is as dry as can be.

So let’s see, Janie said, He’s a Chinese boy and he works in the kitchen. Clay didn’t tell me his name. He said, You know Miss May’s goin around with some boy in the club kitchen and Mr. Victor ain’t too happy about it.

May put the cigarette to her mouth and blew the smoke over Janie’s shoulder. Mr. Victor got his own recreation.

Recreation. Huh. Janie kept the hand at May’s waist calm and polite, a church hand, her mother’s hand writing out a list of errands at the kitchen table. Is that what you call it.

It ain’t what I call this. She moved closer and Janie turned and put the smoke back between them. The only light was in the kitchen and the streetlight that came through the rain and the blinds. Somebody else’s music was playing a few walls away and Miss S’s thunder made it small, and the bottle breaking in the street outside and somebody thrown up against a grate.

You remember that part in Miss S’s short, Janie said, Where she’s standin at the bar and Jimmy Mordecai comes back, and even though she just busted in on him with some high yella chorus girl and he left her on the floor she goes right ahead and dances with him.

Mmhmm.

And you remember the next part.

Mmhmm. May danced them over to the filled glasses and put one in the hand with the cigarette and sipped it and put it against Janie’s lips and she drank. Miss S find you, Janie kept thinking. She find you wherever you go.

He just doin it to take the money from under her dress.

Mmhmm. Is that what you think I’m here for.

How’s business.

Business is fine.

What you want then.

I want this. She put her lips to Janie’s cheek and kept them there while they danced. Rain rain rain, Don’t rain on me all day, the piano coming up like the words you won’t let past your mouth, and so much room in every note you could walk around in it for hours with her showing it to you. You could live there.

When the needle ran into the middle she pulled away to lift it and Janie could feel the warm print of where she’d been get cool; she filled the glasses and May looked through the records. God bless this Victrola, May said and they toasted.

God bless your daddy who left it God rest his soul, and they drank again.

God bless your mama who wouldn’t have it in the house, and again.

God bless Mr. Dent who gave it to you.

God bless your daddy who made some smart money and brought it home.

God bless Isaac Murphy and Salvator.

Amen, and again. May slipped a record out of the sleeve and put it on and lowered the tip of the needle and Janie watched her. Mrs. Pink, she said, turning to her as the piano started barrelhousing slow through the room. I ain’t the only married lady round here.

No mam. Now she let her come close enough to be somebody she’d danced with a time or two, somebody whose nickname came out in a story she told.

And I ain’t the only lady with recreations.

No mam.

And I ain’t been away so long.

No mam. But the last Monday into Tuesday she heard that key was at the end of the summer, and it seemed like a long time ago now.

Then why you gettin all mad at me.

There ain’t nothin I can do. Or nothin I can say. Janie sang along blurry and down an octave. That folks don’t criticize me.

That’s right, May pressed against her, You tell it Miss S.

But I’m going to. Do just as I. Want to anyway. I’m sorry Mama, she thought the way she always did. I’m lettin this church hand go.

Come here, onion girl, and Janie put one hand behind so she could feel her ribs under her dress and May put her cool fingers behind her neck and kissed her. Let’s practice a little, she said that first time at the back of the club while Jake was playing, and some afternoon a long time later Janie was fucking her with her hand and asked her, Is. This. Practicing. She was breathing fast and making sounds instead of words so Janie had to teach her, Say no. No. Is this practicing. No. She tasted like gin and the cigarette and the rosewater she kept on the back of the toilet; her tongue was slick and warm and made Janie think of the little needle she set down and then the music and the place like that under her dress. And don’t care if they all. Despise. Me.

The time on the playground she was getting into the white girls’ jumprope game while Janie watched from the other side of the yard; the white girls turned the rope and jumped in sometimes two at once and May waited at the edge and then took off her sweater and put it on the ground. She got in line and nobody paid attention until she came to the front. They started looking while she moved her head with the rope, up and down to see the opening and jump in; then she did, and Janie remembered her white socks and how they fell below the bones of her ankles as she kept getting out of the rope’s way, her hands held out and her hair flying, and the white girls stopped turning and saying their rhymes. Janie’s mother said her hair was like that because she had no mama. Once when she came over her mother brushed it a long time and put it in braids. Then one girl twirling said she wasn’t holding the rope for a chink and threw it down and the teacher rang the bell for them to come back in, and when May went she forgot her sweater and Janie came after and picked it up. The yard was dirt and the white sweater was dirty before she took it off; it was a cheap sweater in the first place, nothing special, worn at the collar and a hole in the cuff and Janie gave it back to her roughly because it made her want to cry. It still made her want to cry, thinking about it. That was the first time she waited after school and walked her home.

All right, my turn, Janie said and picked what she wanted; she put the needle down and it got slower and she could hear the people arguing in the street but not the words and closed her eyes. Yes, yes. She let May give her the cigarette and breathed it in and gave it back and took her in her arms; the trumpet was still like scatterings of light over water but the voice was from under the water this time. Miss R gonna tell you about yourself now, she said, and May laughed into her neck. And don’t be gettin lipstick on me. She’d been away since the end of the summer. After Clay was born it was three months or so, and when she married Victor it was almost a year. Every time Janie thought of what she’d say when she came back, how she’d answer the door and pretend not to recognize her; every time the days were long and at the end of them they fitted together just the same. She told Jake when she married him; You know I ain’t gonna be that kind of married, she said. You know May ain’t gonna stop comin around, and he looked at her as if she’d said, Don’t forget now, After we get married I’m gonna keep breathin air. You think I don’t know who I’m askin, he said. He always looked funny sitting with his hands in his lap without a piano in front of him. See See Rider. See what you done done. Lord Lord Lord, her lips against her neck and her thigh between her thighs, less and less between them. Janie danced them over to the door and pushed the bolt through and leaned back with one arm around her waist and started the buttons of her dress. Made me love you. One, two. There were six of them. Now your gal done come.

I’m goin away baby, four, five, six, Won’t be back till fall, the light in the corners of the room where the smoke drifted part blue; saying it over was never really saying it over, after the first time so good you wanted more but when it came it was something else, something new. Goin away baby, and May undid the white buttons down the front of the black pajamas, Won’t be back till fall, and Janie pulled her dress down her shoulders and it fell to the waist gathers and she reached around and unhooked her bra and dropped it on the floor. If I find me a good man. She pulled her close again and smiled because it felt good in the same place that was sore while she washed the dishes, and Madame R saying Mmhmm, You got all night to get it all up in there. Won’t be back at all.

Get off me. When the record stopped they could hear it from the street, a woman’s voice. Get off me. The streetlight on the floor had just the blind stripes now and not the flickers from the rain.

Don’t tell me that you dumb bitch.

Get off me. She was drunk.

What’s next, May said. She was standing with her back to the window and the top of her dress down, the streetlight touching her shoulders, her face turned away from the kitchen light.

Let’s give Mr A a turn.

All right.

I’ll get off when I’m good and ready you stupid bitch. He was shouting. May put the record on and they could still hear him in the crackly silence before the music. What you think I brought you out for.

The trumpet played for just a minute and disappeared and Janie took May’s face in her hands and kissed her chin and her cheeks and her closed eyes; she was remembering the first time after the wedding, when she was sitting at the kitchen table at eleven o’clock on a Sunday morning and heard that knock on the door. They were still down on 37th Street by the river; it was June again and bright and the breeze smelled like the sea. Her parents were at church and Sammy was sleeping; Janie opened the door and there she was in the hall with her hair pinned up under a hat with a veil, her arms bare and her lip cut and two black eyes.

She and Sammy and her father went to the party after the wedding because Mr. Dent gave it and her father said they should; she danced with Sammy and watched May dance with Victor Chin, the man her father picked out for her. Her father was sick and he wanted somebody to take care of May and run the kitchen after him; after the wedding Janie started to work in the office and didn’t go to the club to hear Jake play except when the kitchen was busy, and she went home before it got late and slow. She saw May a few times but always from the back, walking down the street on Victor Chin’s arm. A few Monday nights when the club was closed she went to parties with Jake when he asked her; they’d walk there without saying anything and he’d trade the bench with the other piano players all night, and she’d lean against the wall and say she didn’t want to dance and take in the music like cigarette smoke and close her eyes. When it broke up Jake would walk her home and hug her and kiss her on the cheek. He’s got steady work, her mother said. He’s a nice man, you can tell he wouldn’t hurt anybody. Ain’t that good enough for you.

Who’s home, May whispered at the door; when Janie told her just Sammy asleep she kissed her there half in the hallway, one hand at the back of her neck, the other going under her bathrobe like they did with the music playing the Sunday before she got married, except this time Janie was afraid to hurt her and her mouth tasted like blood. She wanted to tear the dress but she didn’t, she went under, first with her hands when they stood against the wall, then with her mouth on the floor, up past the stockings to where the dark hair started and between the lips with her tongue like somebody dying of thirst, trying not to make any noise. May held her head and rocked her hips against her face and came so fast Janie hardly had time to get started; May pushed her away and then she was crying and not quiet and Janie heard Sammy pull the bedroom door shut from his side. I ain’t coming back here, she said, and Janie held her and kissed her forehead and her lips softly and her hands, the right knuckles swollen and the left with the new ring, and said, Oh yes you are. By the time they moved uptown she’d married Jake and May came every Monday night for a while. Victor’s got a white chorus girl, Sammy said. That’s when she started to come around. May’s father had a white chorus girl too. He had a picture but he never told her name. She lived with him in the apartment when she was pregnant and died the morning May was born.

Was that still Mr. A with the mute? She couldn’t remember, but then he sang. When Clay was playing with Fletcher Henderson she and Jake would go down to Roseland and pay their dollar to go in the colored door and watch the back of his head; five thousand white people danced and they let the colored musicians and their friends stand up backstage and take turns at the little window to see out to the bandstand and the floor. When Mr. A was taking them to school it didn’t matter as much, because he played so big you could hear him in the street. Fletcher only gave him little places to tear around but he’d say Listen, I got things to do here, running over the bars, waiting like he had all night but then not one more second and he’d pour it all in, up to the high places where the firstchair man jumped maybe on a good night, staying and playing like dancing on a beam hanging from a crane. Some of the other boys drank on the bandstand or looked through their charts but not when Mr. A was playing. The dancers stopped and people waited outside in the street to hear the next thing he might think of to say. Fletcher thought he was country and they made fun of his mouth and called him Dip; but he had so many new notes in there you could hardly find ears enough to listen, pouring Mr. Henderson’s rice pudding full of good riverbottom dirt and gravel, pouring out his big heart like the first free man. He’d sit down when he was supposed to but you could see the back of his head saying, I been waitin a long time here, gimme some room.

My days have grown so lonely, he sang with the mute cornet behind and they couldn’t hear the voices from the street anymore, For I have lost my one and only, but it was like he was speaking a different language underneath and the words were just the flags he put up so other people would understand. May had her cool arms around her and her hands under the waistband of the pajamas and Janie lifted the bottom part of her dress so she could touch more of her skin. I still am hers body and soul, jumping all up and down where he wasn’t supposed to; You still awake there? she said.

Mmhmm. She kissed her and Janie put her thumbs in the garter belt and pulled it down and May took her mouth away. You keep doing that, she said, and I won’t be able to stand up much more, and Janie kissed her again and kept one hand behind and put the other in front where she was wet and two fingers inside, and May made that sweet sound and said her name. The streetlight was in her face and she wasn’t young anymore and Mr. A was singing about a winter that’s gray and old, An echo of a tale that’s been told in notes he made up in his own throat, Just a second I ain’t done yet, An echo of a tale that’s been told so often, and then a little of the horn choir behind to give him time to get the trumpet up to his mouth, and he played so clear and new, like sun coming into the room, so you blinked in the little silences waiting and your body leaned forward for the next, and he slid up at the end to where you didn’t think he’d go. Mr. Henderson wouldn’t let him sing, so they’d go on Thursdays for vaudeville night and he’d do Everybody Loves My Baby and clown and joke and never come out of the time even when he was talking, like he kept it in those big policeman’s shoes and it came up through the bottoms of his feet, the pulse like the one in May’s bottom lip, in her clit at the end of Janie’s tongue, in her cunt when her fingers were way inside, at the side of her neck when Janie fell asleep with her mouth there. Gimme some of that sweet mouth, May said.

Janie kissed her. Here it is.

You know what I mean. The needle was bumping the label.

All right. Let me just put somethin else on.

She went to the window and pulled back the blinds and looked out, but there wasn’t any morning yet, just the puddles drying up on 138th Street and one slow car hissing by. She filled the glasses and put the needle down and they toasted and drank, To Mr. A, while he did that thing he did at the beginning, because he couldn’t help it, because he was young, the opposite of reveille, going all over making new roads wherever he went, so your ears kept just a little behind asking where no matter how many times you played the record, until he’d made enough roads for the rest of the band to walk down and they came in slow and followed him.

They ought to play that at the post of every race ever run, Janie said, And use it to wake up the soldiers. To Gallant Fox, May said and they drank again; the piano tromped like a tired park path gelding and on the trombone’s turn the drummer did something that sounded like iron shoes against stones. She was too young to bet on Salvator but she watched him, and Isaac Murphy high and light on his back with the whip under his arm, whispering in the horse’s ear and gliding across first by less than a head like they’d done it before in a dream. When she shook his hand it was capable and calm, like Jake’s hand when Sammy introduced them. She didn’t know Earl Sande but she took the train early to watch Gallant Fox work out at different tracks in different weathers; she wrote down his three-furlong times when he was two and bet on him when he was three. Before Aqueduct in the spring she went to the pawnshop on Lenox Avenue and stood a long time outside the window of curtains and crutches and clean diapers and guitars before she went in and put down her mother’s clock and painted plates and the ratty stack of her father’s pictures, Murphy and Salvator, Peter Jackson with his calm fists raised. Gallant Fox was a big bay colt with a wild eye that scared the other horses; she picked him to win on all her tickets and watched his ribs rippling under Earl Sande’s knees at the wire when he tore across with the others four lengths behind. She bet him at the Derby and the Preakness with neighborhood bookies and listened hollering at the radio and bet him at the Belmont herself at the beginning of June and came home with so much money she was afraid and hid it in five different places. May told her she was getting old and she’d better be careful she didn’t forget where her treasure was buried. She’d had a little something in the bank but when the crash came it was gone. She thought she was cursed then and threw out the dream book and didn’t even play the numbers anymore; but then Gallant Fox decided to run and let her come along. She had a ride up to Saratoga for the Travers but she ate something bad at one of Jake’s parties and was too sick even to call the local man; and he lost there, the only time he ever did, and she knew it was because she wasn’t there.

Mr. A and the tenor were trading bars; he was making roads into all the little towns and wandering them, and into the rooms where people were arguing and sleeping and cooking and hurting each other and making love. She walked May backwards to the edge of Clay’s bed in the corner. Maybe you ought to go, she said and May laughed. Maybe you’re missin your kitchen boy.

I don’t want to dance with no kitchen boy.

That ain’t what I heard.

You don’t hear so good. She kissed her. I want to dance with this girl right here.

You been dancin with this girl a long time.

She knew her. Sometimes it seemed like she’d known her since before they were born. The piano was making quiet ripples then banging and soft again and May lay against a pillow and sipped from her glass and touched her head and watched. She knew how to hold her so she couldn’t move her legs and how to take the skin along her thighs in her teeth and how to find that sweet place with her tongue; she traced the length of it and he played that long note that made you want to shout when he stopped, running over all the bar lines and slowing everything down toward the end. The needle hissed and when she got up May groaned. She’d left her watch by her shoes and the hands were in a slack L for five. Just one more, Janie said.

The drums and the bass took it down first and when he came in with his horn he brought it up, but deep and slow, like a happy funeral, like a woman falling down drunk laughing with tears on her face; she knew her, she found the place that made her happy, just at the tip, and played there with her tongue, staying and going away, keeping on and waiting, up and down, back and forth, the rhythm of her mother’s fingernails tapping the table, of her mother’s clock ticking on the shelf, ticking on the pawnshop man’s counter so she could prove it worked, of the curtains and blankets she passed on the way flapping against somebody’s furniture put out in the street, Salvator’s hooves, the jingle of tack in the old stables, the snuffling in the curbside troughs when they drank, fans ruffling the club kitchen calendar pages, rats in the wall, the bell over the sweetshop door, the hall toilet running on and off, pigeons scratching the sill, the shovel in the hands of the man who dug her father’s grave. Then he was singing and she remembered the first time she saw him from the front, uptown late someplace small where nobody was white, how he’d lean his head to the side and close his eyes, that Mmm when he was getting ready to go somewhere maybe nobody’d ever been, how his smile was private or covered something private even when it seemed like he was giving it away. Cold empty bed, Here’s all of it, Wish I was dead, but the other language underneath said Mmm, What did I do. To be so. Black and blue, he sang it three times, black the first time clear and plain, the second time blurred and falling, the third time a shout, after he made that design in the silence, Cause I. Can’t hide. What is in my. Face, writing the shape of it in the air so you almost couldn’t remember the word he started with. When he played he didn’t smile; he’d listen and start to blow and close his eyes and when he opened them his look was like an arrow, then wait again with his lips slack listening, the spit and sweat rag next to the shiny cufflinks, one hand holding the trumpet firm without moving and the other pretending to have something to do with what filled up the room when he played.

It seemed like a little place, like no place at all, but so many ways around if you knew. She rolled her head and let her tongue go wherever it wanted, down every lush path the day said wasn’t there, breathing the smell of the beginning of the world, of every secret thing; when she came in her mouth Janie kept it, the familiar fingers gripping her shoulders, the pulse of useless joy against her tongue, for the days she had to walk in the barren world, the days she had to live without this.

She wiped her mouth on the back of her hand and lay down and May reached and found her and touched her, quickly, when by then she could’ve come just looking at her face. Before they fell asleep she whispered against her neck: You think we’re gonna stop this when we’re dead, she said. We ain’t.

When she woke up the machine was hissing and a key was scratching the lock. In the little light May’s face looked gray, like Jake’s did in the mornings when he had to stop playing and go home. The lock clicked and the door banged against the bolt and someone cursed it. Ma, you in there? It’s Clay. He rattled the knob, What’d you bolt the door for? It’s me, Lemme in.

Fragment 6: In Which Henry's Brother Hugh Shaw Keeps Sheep

Sometimes when he was lucky he could become them: the curled horns, scarred udders, black muzzles trembling over the grass, the oddness of them after shearing, eyes far to the sides of suddenly large heads, impossible to face front and look them in the eye. It was quiet there and he'd been in them enough to know; he could stand for hours serenely, then dodge and twist and skitter and run, with no human eye watching, stop to breathe and rest and lift his tail while making meat and milk and a quiet soul from grass. He tried to stay in them as long as he could, but something always fetched him out, hunger or the end of a long drunk and his fire out, or a neighbor wanting wool who would call him Hugh; then it was finished, and he'd inspect his cracked caked boots and the dents of his knees in his trousers and his hands like someone else's, years younger from touching the oiled fleece, and he'd find no sheep but no man either. Behold, he would say, running a soft palm over his hard beard, I am a dry tree.

He walked after them at dawn up into the hills where the grass was drier, after straddling the ewes by the big steel tub one by one out of the pen, dipping a cup for his breakfast. He'd lost two ewes at lambing and could still see the gaps they left, near the orphans he'd disguised in the skins of two lambs who died, the new wet coats tied on with twine and the ewes sniffing and letting the strangers suck until after a day they became their own. Away now! he called when the front of the flock reached the patch boundary, and the black dog raced there and edged in the leaders; Come by me! and the dog raced the perimeter and barked them back toward the center; and Away again and Come by and Down now, and it was quiet except for the crows and the bees and the sound of the grass torn from the ground.

It wasn’t much; he saved the thick green and the water for the afternoon, when they weren’t as eager and wouldn’t colic. He walked among them and looked at their faces and started conversations; he stood straddling them and raised the lids from their eyes. Good morning, my soldiers, he said as he checked the knee shear-nick and rubbed in more salve, Tell me your dreams, A carriage to carry you? Acorns and leeks? The wolf? and he jerked forward to startle them, Ah yes, the wolf, and they turned and started a new patch a little away from him. He watched the ewe he'd found stuck in a fence overnight last summer, and the dozen he'd put to one neighbor's ram and the dozen he'd put to another, and their lambs, which leaped and which not, which ate harder; he watched the new wethers he'd made after lambing, squeezing the balls out of the sacks and cutting the thin cords, rubbing with lard and feeding them richly after. How are you, my prince? he asked one, squatting to hold a leg and touch the empty scrotum, the lamb reproaching him with one eye over its shoulder.

At the end of the morning he moved them lower and he and the dog settled them again; he took his bowl of oats to the oldest ewe and bled her with a flick of his lancet and staunched the seep and mixed the pudding with his finger and poured half beside him on the ground for the dog. The sun was warm and the part of him that worried about the cold after shearing rested. He took out his flute and played for them and watched the pitches make the dog's ears move and the lambs wobble-run and return to their mothers, and had the little bit of whisky he permitted himself before the summer and leaned back and closed his eyes.

He'd played the fife for the soldiers; he supposed he'd been a soldier himself, although he'd lifted no gun. He wore the uniform and tramped and listened to his stomach growl and ate swill with the others, when the British raids neared Washington and they called up the militia. On the afternoon of their debut the redfaced officers shouted them into position and he played and so did the drum for there must be music, and the others spit grapeshot into the fancy red troops from a ridge behind some Potomac village; and as the smart ranks surged forward like a wall of blood they all ran, before the spectators and Cabinet members, and the British waltzed into the capital and burned it and only Andy Jackson at New Orleans stopped them.

It was all the same to him, he wanted no part of it; they'd be walking that much sooner home, and no one to limp or bear on a litter or leave behind in the ground. But that night James Jones wouldn’t come with him to the edge of the camp where they touched each other in the dark. Something had changed. In the first days of the drill James Jones mocked it; but the years passed and Henry let him go at the mill, and he had to return to his father's crowded house. Hugh would walk there in the night and tap at the kitchen window and they'd lie under the roof of the leaning barn until it got too cold, but James Jones would rarely smile for him anymore. When they called up the soldiers he volunteered to walk among the farms to tell each man when to assemble; when he arrived at the camp someone said Here's our ma who's called us all home! and he knocked the man down and had to be held by the elbows. After that the jokers and malingerers hid from him. Sometimes he smoked with the captains. He'd begun to have hopes for soldiering, and after the retreat saw them broken. He’d run with the others. When Hugh came to him there were tears on his face and he turned and pulled up the rough blanket to hide them.

What is it?

Go away from me.

Hugh put a hand on his shoulder and James Jones shook it away.

It's just a game, Hugh told him. Now it's over. By the frost we'll be home. Again he rested his hand, and again James Jones flinched from him.

Home is nights in the kitchen corner like a dog, he whispered.

Home is this angry thatch of hair, Hugh thought, This chest he has his arms curled around. He put out his hand again.

No! James Jones hissed, sitting up and flinging the blanket aside, Are you going to make me say it? Get your hands away from me. He looked him in the eye and Hugh could see the reflection of the dying campfire and the shapes of the other men sleeping on the ground. One stirred and Hugh started sharply, his heart pounding, the way he used to start from sleep in the cottage and look for the morning light. Shall I raise my voice? James Jones whispered. I am not that man, he said, looking in Hugh's eyes. Go away from me.

He married Betsey Markley in the spring. Hugh heard the plans for it in the winter and froze his face for the neighbor who told him and swore he wouldn’t but he walked to the house in the middle of the night through calf-deep snow, swimming in whisky, to sob against the window but he wouldn’t let him in. In the morning the trudged path between them was there for all to see and his brother banged on the cottage door until he answered and sat on the edge of the bed. Hugh laughed and suggested a legal proceeding and covered his face with his arms.

They lived on her father's farm and came every spring for the shearing and they'd made eight children. The sons who had tugged the sheep to the bench for their father sheared themselves now, and only the youngest rode holding the rams' horns. James Jones and his wife arrived side by side on a cart bench; Hugh watched for signs of tenderness between them, and finding them or not finding them made the same ache in his throat. The shearing was just done and it was still fresh: the gray beginning in James Jones's hair, the place where his collar opened against his chest, the lines at the edges of the eyes that wouldn’t look at him.

He leaned against the tree and the sun fell and the chill started to creep from the ground; it was time to walk them home but he wouldn’t yet. He was a boy at the beginning, James Jones, the thudding of his name in the ewe's bell, the night they first touched each other, at the edge of a husking party. Hugh was unbuttoning himself to piss in the dark, blurred with whisky and dancing, and James Jones came and stood close behind him.

What's this? Hugh asked, startled, fumbling.

You know what this is, the boy said, and pressed his body along Hugh's back.

Hugh turned. You don’t know what you're doing, he said. In the dark he could see the flicker of the boy's smiling.

You'll teach me then, James Jones said, and pulled their mouths together.

But even then it was the same, Hugh remembered. They stood because the ground was cold. When they returned to the light and the dancing they walked as if they didn’t know each other; on the barn floor they stood in the provided places and took the hands the dance assigned them and whirled away from the smell of the darkness under their clothes.

He stood up and stretched against the stiffness. Every year the lambs fetched him back to the world, after the winter, which he tried to pass in a whisky dream, waking sometimes to a scratchy beard and the fire dead and bits of broken crockery on the floor, the dog whining and sniffing his face. Then he'd walk to the big house in the snow, the sound of it hurting him and the light in his eyes, and when he rapped at the back door with his ash can one of the servants would drop two coals into the scraps of tinder and hand it back to him.

Come by me! he called into the shadows, following the dim white trail forming. He wasn’t alone; he had his prosperous brother, his flute and his flock, his dog and the flask against his palm. When he drank a fire passed down his throat, kind enough if he persisted to touch every part of him and consume it, leaving only damp ashes by morning. What had he done to deserve such mercy? He was Squire Shaw's brother who lived in the cottage. The men in the tavern knew him. When the war summoned him he went. He and his friend had fallen out. When he died his brother’s children would bury him and pay someone to write his name on the stone. He was Hugh Shaw who liked his whisky and kept a flock and had no wife.

Fragment 10: In Which Robert Shaw The Congressman’s Son Listens to the Ghosts of Washington and Finds His Truest Contribution To The Land Is Departure

He had found almost enough ways to escape (A muddy creek at the base of the hill): across the Hudson to Albany by stage (Tall woods at the edge of an alder swamp), a canal timber barge to Buffalo (The marshes where Negroes hunted stray cows with bells), a steamer from Buffalo to Sandusky (Stiff clay, dust in dry and mortar in rain), a wheat barge inland to Milan (The city trees cut by the poor for fuel), and on foot to Norwalk, in the Firelands (Twin white stone boxes on a heath of stone dust), where he followed his father's interest (The Rotunda to recall a Roman temple) as perfunctorily as possible (How the gentlemen fished in the Tiber). Even marriage hadn’t stopped it (Ground floor committee rooms); once he had installed his wife (Second floor chambers and Rotunda) on the farm in Chautauqua and paid the hands (The furnace room and the privies in the basement) and begun the performance of his husbandly duties (The cloakroom where they spoke frankly to one another), he could still leave southwest from Sandusky by train (Those blasted Six Nations niggers) or ride the rafts down the Allegheny to Pittsburgh (The downstairs refectory, Beefsteak 25¢) and follow the river however he liked (Mutton chop 12 1/2¢ , 6 1/4¢ whisky) to Louisville and Cincinnati and Cairo (The House of Representatives the lounging place of both sexes) and up the Mississippi to some Front Street hotel (Where acquaintance is as easily made as at public amusements), without causing the wrath of all Berkshire County (The page boys carrying messages) to descend upon him. The card tables (The gentleman asleep with his feet on his desk) were a kind of leaving, the study of the men's faces (The mail just arrived by stage), the way he could forget himself in the terror (Knuckles rapping the sand off wet ink) of the question, Is it you (The gentleman passing with his crop and hounds) to whom I will lose everything? The whisky (The gentlemen quarreling and sending their seconds), sleeplessness, the lines scrawled on scraps in his pocket (The gentleman pale after his dawn rendezvous)--I can see her standing there,/The light on her unfastened hair (Pitchers of water and tins of snuff)--the girls who sat on his lap and came upstairs with him (The newspapers and documents on the floor), all of it helped, against the moment (Cough loudly, scrape feet, bang the desk cover) he would have to say Robert Shaw to the clerk (Point of order, point of order, sir) and collect the letters from his wife and his father (The motion of the Previous Question). Sometimes now he made his brother do it (The question cannot be debated until the House consents to hear), his Junior, his Harry, his Hank, his Hen (The Speaker on a high dais like a throne), a hundred names for him, all but his father’s (The crimson draperies hanging to the floor), partner of his long confinement (The chandelier, the burnished sconces), the only person he couldn’t leave.

Since he had failed at his studies of law (The plan of removing the aboriginal people) he had been sent to the Firelands (who yet remain within the settled portions), where his father had accumulated (of the United States to the west of the Mississippi) many contiguous five-mile squares (approaches its culmination). He was to oversee the wheat planting and harvest (It seems now to be an established fact), which meant he disbursed his father's money (that they cannot live in contact with) to the men who knew what they were doing (a civilized community and prosper), and in the tavern hired others with flails (The past we cannot recall) to beat out ten bushels a day (But the future we can provide for) on a barn floor all winter. He followed the shipments (With the exception of two small bands in Ohio) through the mills and kept track of them in a ledger (and of the Cherokees) and rode with the horse wagons to Milan (all the tribes east of the Mississippi) and drank with the teamsters and walked the tow path (have entered into engagements which will lead to their transplantation) with the barge up the canal to Sandusky (Such are the arrangements for the physical comfort) and conducted his father's transactions there (and moral improvement of the Indians), the barrels to Buffalo and Chicago (The country destined for the residence of this people); he put the money in the Norwalk bank and wrote (shall be forever secured and guaranteed to them) for permission to draw his share, the system (The greatest question ever before this Congress) his father had insisted on. When he proved (Communities of men whose fate is wholly in our hands) trustworthy it would change; but he loved his jaunts to St. Louis (The world would lose but little) and so he was twenty-five and the system was the same (if these people should disappear).

His brother had only recently completed his failure (If the American character may be judged by their conduct) and had been permitted west in the early spring (In this matter they are most lamentably deficient) with ten dollars and three letters of introduction. He insisted (In every feeling of honor and integrity) on coming by land and finally appeared (We may call upon the rocks and mountains to hide our shame) at the Norwalk hotel with a beard and a dollar (Passing from the savage to the civilized condition), reeking of stables; Excuse me sir, he said (The absence of the meum and tuum in the community of possessions) after pounding on the door, Where's the lively cuss (the grand conservative principle of the social state) called Overseer Bob, I hear he bosses baths around here (causes the chaos of savage life), have you seen him? And Bob said Right spot, young man (Common property and civilization), but you'll have to leave your horse outside, I know (cannot coexist) you're fond of her, but rules are rules, no shamming (They must either conform to the institutions of Europeans), I can smell her right behind you (or disappear from the face of the earth); and Harry threw his arms around him (The gentleman from Massachusetts) and said How've you been, old man (The gentleman from Tennessee), and he answered, Waiting on you, little brother (The gentleman from Virginia). Let the revels begin.

He had never once left his brother, even when he was parted from him (The gentleman from South Carolina); he carried his joking voice in his head (Alpha and omega of the ethnological chain), as he carried the smell of the gold Berkshire meadows (The hunters found intractable at catechism) in autumn and the mill girls around his cock (Extirpate with mounted regiments) and the reeling joy of the holiday dances (In a little more than one hour) and the dark lake against his skin (five or six hundred barbarians) when he and Harry would swim at night (were dismissed from a world that was burdened with them). He left his mother only briefly and always returned (Thus by their horrible pride) to the curve of her mouth with its hidden mischief (Thus they fitted themselves for destruction), her lips at his forehead when he was ill (Here's to the man who steals the most land tomorrow). It was the law that required leaving (without being caught at it), that wrapped dry hands around his throat (As if want of strength had destroyed our rights) in various disguises: the school's rote and drill (For a little money paid to a few men in our Nation) and hollow pronouncements, his father's scratching quill (God has placed us here to be punished for our sins) and beatings and lectures, his father's appraising (For this purpose he makes use even of the heathen) company, after they had assessed the stock (We were hedged in by evils), Ah, Henry's eldest, there you are (and chose that which we thought least). There he was not (You have set me on your enemy as a hunter sets a dog on game).

In Norwalk he and Harry made quick work (Mild republican institutions) of the seed purchase and planting and arrived in St. Louis (And be it further enacted And be it further enacted) in the middle of the night drunk with the barge crew (No Indian or descendant of any Indian) and slept on the dock; when he opened his eyes (shall be deemed a competent witness), Harry was sitting with sun on his back (The Indians' bones must enrich the soil), hair sticking up, elbows on his knees (before the plow of civilized man can open it), watching the river. It's something, isn’t it (No man living entertains kinder feelings) Bob said, yawning, and Harry said (to the Indians than Andrew Jackson) Here you are, poet, and cleared his throat (Cowardly Perfidious Vain Effeminate): O great wide river far from clear (If any deserves the appellation Friend and Father), Call across you and no one will hear (Brave Cruel Incapable of systematic thinking), We leave you now to fetch a beer (It is he who is now at the helm). Just before waking, Bob thought he heard (What use do these ringed spotted cattle) a deep rumbling in the waters, half in a dream (make of the soil? Do they till it?), the sound of something heavy and restless and old (Revelation said to man, Till the ground), turning over and over; but when they stood (This alone is human life) he could hear nothing but the rivermen calling (Teach him agriculture and reduce him to civilization) and Harry's laugh and the water lapping at the levee (The land is everlasting) and his heart marching (The few goods we receive for it soon worn and gone).

This afternoon he'd woken up late (They asked for a small seat/We took pity on them), with a swollen head and a terrible thirst (Shall be covered with cities and the fields of white men). The sun was slanting in the window already (To plow the ground shall I tear my mother's bosom) and Harry was washing with his back to the bed (To dig for stone shall I take her bones). The sound of the water had woken him (To cut grass and make hay shall I cut her hair). Morning sir, Harry said, I have drawn your bath (I give up all good clothing/I take scanty blankets), and chucked his shaving brush in the basin (And cut them in two/I crop my hair) and winked into the square of mirror on the wall (If you leave the land you become a stranger) and turned his attention back to his chin (The dead wander away and never return). His back reminded Bob of his father's (A handful of wild half-naked thieving), narrow and pale, when he was young (savages dignified with the attributes of nations); once on an errand of his mother's (Kill the dancing Indians) he unfolded a square of paper from a drawer (Instead of a stone I use a sharp axe) and found a drawing, she must have made it (Instead of my own warm ancient clothing), of his father, sprawled asleep (The beaver flee/The springs dry up), looking like no one Bob had ever seen (Singing his death song with his arms folded). His cheeks burned and he folded it closed (And be it enacted that the first of June) and hid it under a packet of letters (all laws passed by the Cherokees) and fetched the needles he'd been sent for (are hereby declared null and void) and handed them to his mother without looking at her (as if the same had never existed) and never spoke of it to anyone.

They went downstairs and it was two o'clock (Manacled and chained together) and they were nearly drunk again by three (The women and children trailing after), at the bar eating plates of fried potatoes (The forced marches sold to private contractors) with the sun slanting in through the glasses (An army of eleven thousand sent). A girl named Elise sat beside him (They will be either civilized or extinct) and touched him and passed her hand over the pocket (The detachments into the villages) where he'd folded his three letters unread (Passing from the savage to the civilized condition). You're hardly awake, he said, What's this? (The people driven to assembly points) She had crusts of sleep at the corners of her eyes (The rotting steamboats and ferries across the Mississippi). How can we muss your hair so early? (We are diminished/The cleared land becomes a thicket) What will be left for us tonight?

He was so far from Massachusetts he hardly spoke English (Certain laws of that state which it is alleged go directly), he told himself, closing his eyes (to annihilate the political society and seize the lands of the Nation) in the wash of the bar languages (We are in the midst of an Indian country); but small things would remind him: a bargirl's child (and the most exposed part thereof in hopes) running across the room and he would miss his sister (of getting lands on easy and equitable terms), or the clink of a toast and there he would be (Men of extensive influence), at the end of the 4th of July parade (who may at all times be counted upon), raising his glass, Gentlemen! (I can permit him to be elected or send you another man) To the lawyers and the political priests! (As a friend to liberty and the permanence of our institutions), his father's gaze on him sharpening (The fatal road which has conducted every republic to ruin), May they no longer play the old game (And when you have perpetrated it go home to the people) of the one hold and the other skin the people! (and tell them what glorious honors you have achieved) And they'd cheered and drunk and he was young enough (for our common country/He turned his head) for his father to whip him later in the shed (and lifted his hand in a practiced gesture), but only just; it had been the last time (and the tin of snuff was brought to him) and soon after plans were made for his departure.

Very well, Mademoiselle, he said to the girl (I have contributed to advance your interest), and saw some tension ease in her face (I have taken the liberty of presenting your name); To the royal bedchamber, he said to Harry (to his Excellency for District Attorney), who clicked his heels and bowed and said My liege (With sincerity I am your friend), and the men near him laughed and one called the barkeep (Gentlemen of the mess I give you our good Mrs. Hickey) and said Let me buy one for the king's brother (At Fletcher's At Brown's At Mrs. Queen's), What's his, and the same for me (The sound of arms cracking in Washington City). He's an eager bastard, he heard them say (When we took up the Chickasaw Treaty) after him, as he let the girl walk ahead (the Indians sat in their quiet council); he watched her hips move under her dress (One walked down the dividing aisle) and heard Harry answer, Oh not eagerness (to the dais to Clay and took his hand), It's benevolence, He's tired but he's sharing the wealth (Could I purchase in your neighborhood), He shares the royal resources as often as he can (a Negro boy ten or twelve years old), Keeps the subjects happy and clears his mind (At a reasonable price/I want such a one) of burdensome affairs of state (to ride out a Maltese Jack of mine). She stood aside and swallowed the last of her drink (She could not read but her name was on a list)--it was her child, the same dark eyes, like his sister’s (A neighbor had provided and she had to go)--as he fumbled for the key and opened the door.

He leaned against the wall the way he liked (The money appropriated for the Removal) and lowered his trousers and she took him (of the Senecas of Sandusky) into her mouth and made his eyes (McElvain the Ohio Indian agent) roll back in his head, he was a king (Henry Brish subagent for the Seneca) and he was erased; before she finished (Those who listened to the agents' enticements) he took her hand and lay on the bed (Two parties, by land and by water) and had her ride him while he thought of a woman (The nine-month journey, well into the autumn) with no face and a cunt like a panther's (Rains and cold overland to Dayton), who would live to do whatever he wanted (The canal boat to Cincinnati, the steamboat to St. Louis), and he came thinking about her long hair (William Clark the Indian Superintendent), while Elise looked out the window with sweat on her lip (Among the elders especially sickness), and it was the sweetness (The deadly haste of the escorting troops) of every departure but only for the time (Not to stop to bury the dead) it took to shudder out his breath (Elk River July 4/I charge myself). Kiss me, he said, and she laughed and stood and dressed (with cruelty in forcing these unfortunate people on).

She took the money from the washstand (B has made a speech I presume will be read with applause) and clicked the door closed behind her (But you can’t imagine how disgusting his manner is); he was not yet drunk enough to sleep (And they shall go forth) and the slant of the light disturbed him (and look upon the carcases of the men that have transgressed against me). In it was the fullness of the day and the promise (Poor Bibby notwithstanding her stupidity) of all those to follow, relentless (makes a nice kind of biscuit); in the shining pool on the floor (She is always delighted when I ask her to make them) he could see the river's reflection (My old man and woman equally faithful), and faintly heard its voice again (On her knees scrubbing the parlor floor), like a groan. His chest ached. He could hear Harry (O Milly it's not such a big favor is it) downstairs, telling some story (A miserably idle dirty girl) and the other men laughing, and footsteps (A fine little girl of five) and horse's hooves and the rustle of clothes (bound to me by Dr. Willis) passing the hotel, the carts creaking (Mr. Calhoun Mr. Savage Mr. Barbour) and the fragments of conversation (Mr. Walker Mr. Porter Mr. New Mr. Shaw). A hundred pounds and it's worth the shipping (At the racetrack the quarreling, the shouting of bets), one man said, You could go two hundred, but of course (No one listens and everyone disagrees) there's the risk, and he remembered the letters (The duel at dawn, the man with the red shirtsleeve) Harry had fetched for him from the clerk (The cheer and hiss of the galleries), in the trousers crumpled on the floor (Liar Scoundrel Puppy The gentleman). He sighed and considered the prospect of supper (soils the spot he stands on Mr. Speaker) and pulled the sheet up to his chest (Expert in the tactics of tedium) and lay with an arm crooked over his eyes.

He had walked Front Street for the first time (In consequence of stubbornness they will moulder away) elated, past the whisky holes (We lounge or squabble the greater part of the session) and gambling houses, the trappers and traders (and crowd the business into the few days at the end), the southern planters and their families (The long trains of slaves down Pennsylvania Avenue), the bands of Indians, the coffles of slaves (He will not learn the arts of civilization), the pickpockets and tavernkeepers and whores (From the Capitol to the Executive Mansion), and no one gave him a familiar glance (And he and his forest must perish together); it belonged to him, he had known from the first (The yeas and nays have been ordered/The clerk will call the roll), he had found his true home, the wilderness (It is moved and seconded that the resolution be adopted), he would never return to any other (The question is moot The question is dead), the edge of the known world, the perfect place to leave.

Fragment 12: In Which Appears Grant Titus’s Wife At Pinkster Time

She remembered it years later, when her hands were stiff, when the late train crossed into Manhattan and her grandson was asleep, his head back and one arm outstretched; he reminded her of a prince they crowned at Pinkster time when she was a girl, who marched behind the king elected by acclamation at dusk, a Guinea manservant to the patroon, dressed in a British general’s scarlet coat. The prince wore a strip of scarlet across his forehead and carried a lit torch as a scepter, past the fish and fruit stands closing as night came on, a brown boy who listened to the black king: You’ve forgot your fathers’ language! the king cried when the boy blinked and shook his head in the rain of strange words; What else you’ve forgot? You remember how to dance? the king cried, leaping almost out of the torchlight, and the boy gathered himself and leaped beside. Then the fiddlers started and the Guinea masqueraders threaded forward in a line, and when she pressed close she could see beneath one costume the gall marks on her father’s ankles and the muscles of his feet, an old man’s, fluttering to lift him a little and set him down. Who’ll sleep in a cellar tonight? the king roared, and they roared back None; for all the week of the festival she saw people sleep only during the day, lying down on the hillside with their faces shielded from the sun. At night they danced, and on the last night ate election cake and drank election beer until morning, when the king took off his coat and they walked back along the roads they’d arrived on, and they and the trampled June hill belonged to the state of New York again.

Fragment 32: In Which Claire’s Nephew Visits His Father In Prison While She Translates The Messages From The West

Adam’s father had been gone half a year (What’s your name the annuity men asked her) and he still woke up thinking he was there (She pointed to the faces flying through the forest), smelling muddy boots and smoke and whisky (Where were you born At the rapids), expecting he’d get up to do the milking (What year), when his mother was still asleep (At the sweeping of the ashes after the war). But the milking was his now; he buttoned his shirt (She went to live with her cousin Lily) and walked through the cabin listening (and followed the dream lines across the earth) to all the breathing that wasn’t his father’s (and stopped speaking their language that moved like a train); outside his old aunt looked at him (Silas Get to that milking or there won’t be any breakfast) from the eastfacing chair where she was never sleeping (Sometimes she stopped speaking any language), with marks in the dirt from walking circles (except the one the dream lines taught her) the way she did that made him ashamed (the language she needed for walking in the sky).

He said the words to the cow his father taught him (She followed the path down the north valley) and leaned his forehead against the warm flank (where potatoes and onions grew in the low ground). When he’d finished he could whistle for Elias (When she passed the fort the men visiting and smoking); in the spring they nicked the cherry bark (after they'd cut down the pine) and dipped the clear resin and chewed it (and taken the weapons from the roots and bloodied them) while they squatted in the woods and gambled seeds (against each other in someone else's quarrel), and played cowboys and Indians like the poster in Salamanca (while a stranger leaned in the doorway and picked his teeth). The cowboy was taller so that part was his (The stranger wore a vest and a watch on a chain) and Elias was the Indian (and they all looked but one man sat with his back turned); they ducked behind the trees and boulders (The seated man wore a scarlet jacket), shooting at each other with their fingers (Perhaps we could sell our mothers also he said) and taking a long time to die on the ground (His stepdaughter was braiding his hair). They made rifle sounds and shouted to circle the wagons (She passed stacks of barked pines some marked with numbers) the way a white boy in school (Children hiding in the burned orchards) said they did in the real show (Far apart along the river the fenced Quaker fields). Come out you yellow savage! yelled Adam (So the men could do women’s work and no one would see them). Say your prayers cowboy! Elias cried (So they could listen to the silence of the animals alone) with his hand cocked to Adam’s temple (The train rained little bits of fire) before he pulled the trigger (and left burn marks on her pockets where the seeds were).

They went to the Quaker School at Red House (She saw treaties in the courthouse beside stacks of rifles) where if you forgot and talked Indian (the drunk men waking up with ink on their fingers) they made you stand in the corner a long time (the stranger patrolling with his machines). He and Elias hadn’t forgotten (All messages from the west) since they learned their letters but they still got in trouble (are delivered through the western door) for other reasons, like the white boys laughing (The lines glowed like paths of fireflies and spoke) and beating against the bench like a drum (They led through lumber camps to the plains). His mother told him not to but he couldn’t help it (Death came from the west Was that the message); once when he couldn’t think of an answer (The white men joked by the courthouse Oh Papa) that white boy whispered Why don’t you ask your father (Coldfoot loves me and wants me to marry him) and he knocked him down and had to stand in the corner again (Oh Papa What shall I say). When he was younger they placed him there quietly (And then Chief Crickinhisback), but this time it was by the back of his neck (says Oh Is his a good family) and Mr. Kraft talked tightly against his ear (Oh yes says Lovely Dove They're all dead). You're going down a bad road, Jacket, he said (She sat facing east listening over her shoulder). Get off (All right then What is it I'm listening).

Your father is the worst poker player in the county (The man they turned to had pneumonia He was dying), his mother told him, but it wasn’t true (with red drops on his blanket and on his face); Adam remembered two different times he woke up (The soldiers lined up and lay on their stomachs) to his father roasting a chicken for breakfast (and watched the messengers and aimed their rifles) after he’d played poker all night (In the morning they planted guns on the ridges), and once there was a row of new shoes (and searched the wagons for rifles and knives). He went to town in the fall to sell corn and apples (The men protested The short rations) but no chickens or shoes ever came of that (and no rifles or knives meant they would starve). His mother wasn’t smiling when she sat him down (The soldiers were rude and scattered their belongings) to tell him why his father wasn’t there (One man prayed and cried and threw dirt from the firepit). I don’t want you hearing this from somebody, she said (asking the eagles to take him instead). Your father made a mistake. He broke the law (while the soldiers went among them taking their weapons and laughing). He's making it up now. He'll be gone two years (clicking empty pistols at their heads).

What mistake. (The stranger with his face hidden)

He took some money that wasn’t his. (passed holding a torch)

Can we see him? Is he far? (a rifle)

He's in Erie. About a day's wagon ride from here. (in the other hand)

How long's two years. His mother sighed. (walking but not touching the ground)

Not so long. She took his hands and looked at them (At Sitting Bull’s camp they were dancing). By the time he comes home you'll be almost a man (because they missed their relatives). The boys at school told it differently (In the Black Hills by the White Earth River). Heard your pa's a thief, one said (The people ghost dancing above Plum Creek).

In the summer he asked if they could go (The dead are all alive again there) but his mother was doing the farm work alone (Then we’ll sit with them and laugh and tell stories) and taking in laundry and she fell asleep early (Dance five days then bathe in the creek). So he waited and picked up his boots (Then the sweetgrass and the digging stick and clear water) and stepped outside barefoot in the moonlight (Silas holding up his fish There will be no more sickness) where his aunt sat watching him in her chair (and everyone will be young again). You're going to your pa then, she said (The flood and new earth like a great wave rolling) and he nodded. She handed him a paper sack (We will dance and be lifted to the mountains) with bits of maple sugar. She made sweetgrass baskets (and come back when the animals are everywhere) and pincushions and gave them to someone they knew (the buffalo and the wild horses) who sold notions to tourists in Buffalo (and the white people will be consumed). When they went to town she bought candy with her own money (Wear this shirt and you will see him) and his mother shook her head. By the place where he slept (Do not tell the white people this) in the kitchen was a row of animals she'd made him (The son of God is upon the earth), a turkey, an osprey, a turtle with no eyes (Around the neck the shirts painted blue). Aunt Claire said she could hear what they said (By the fort she heard voles and milksnakes in the grasses) and if he learned he could hear too (They came to the starving dancers’ camp); but she walked in circles and talked to herself (for Sitting Bull The Indian policemen) and people said she was crazy. Even his mother said it (riding in from the Agency), She's a little crazy sometimes. She had a boy (with orders to arrange his arrest) a long time ago who died. Your Grandpa Sam knew how to talk to her (If they try to rescue him kill him) but he's gone now. She's your grandpa's cousin (The ones from the boarding schools could read) and don’t let me catch you disrespecting her (the newspapers and said this was planned for them). She's old. She'll just be staying a while (By the early morning he was dead). Sometimes she stood with her hands together (Our safety depends on extermination) and threw her arms up in the air (Wipe these creatures from the face of the earth), as if she were setting a bird free. Sometimes (Straight east of Cherry Creek) she combed her hair and seemed fine but still (Straight east of Cherry Creek across the river) he lagged far behind when they went into town (To see the murdered relatives Dancing in a circle) because he didn’t want anyone from school to see (The cavalry camped on Wounded Knee Creek).

When he was little she brought him into the woods (Before the shooting started the soldiers) and showed him the split milkweed pods (separated the men and made them stand together) and told him they were full of messages (They wrestled with a deaf man) and he listened with the seeds against his ear (who wouldn’t give over his rifle and knife). They had their own language and his mother didn’t like it (He’d had a war pony and sold it for farm tools) and punished him if he spoke it in front of her (People said he was a little crazy sometimes). His mother grew up Baptist but she never went to church (This is what we think of councils); her brother got beat up once (Someone brushed against the trigger) trying to bother the longhouse people at midwinters (and the rifle fired into the air). Aunt Claire said he should listen to his mother (Strip the loose cornhusks and dampen them) and they could speak their language when they were by themselves (Clean away the bits of insects and dirt). Once about the time he learned to read (Fold twist and bend Give it scraps of clothing) she spoke it to him by the river and he couldn’t understand (No life); then he started to run around with Elias (until a child tells it secrets) and they didn’t walk together anymore (No face Strands of silk for hair).

A handful of messages, she told him (The rifles cracked The guns roared from the ridges), the seeds spread across her palm (The ravine plum thickets The gulch filled with smoke). She kept them in an old tin box. His mother and father (She walked and listened She watched a pregnant woman running) kept three apple trees and a field of corn (From the top of the hill the big bay horses) but they never used any of Aunt Claire's seeds (the riders leaning down to swing their long knives); even when there was no money and they had to grind the seed corn (The men whose weapons had been taken) and didn’t know what they'd plant (The women and children The little village) they let her carry the tin box under her arm (A stranger flipping open his watchcase) and spill the seeds and arrange them in patterns on the ground (calling the guns by their proper names). He used to do it with her when he didn’t know any better (rapping sand from a document); there were apple seeds and kernels of red and white flint corn (walking a handsbreadth above the ground), flat squash seeds and specked beans. One winter afternoon (The moon of popping trees) on the floor by the fire they made a river meadow (The guns rattling through the death songs) in the spring, where it was warm and you could lie on your back (Spirits blowing ashes on their grandchildren) eating strawberries with the sun in your face (A woman with a doll she made). She made the river with apple seeds (A woman with her braids cut off). They'd been in the tin box a long time (She watched the pregnant woman run). His mother said they were dead (to the edge of the thicket and miss her footing). Seek-no-furthers, Aunt Claire said, pointing (and stumble and they shot her there). That was their name. She gave him some (Sometimes they shot each other by mistake) and he gave some to Elias and they played a game (the soldiers flushed attentive eager) to see if they could get them away from each other (as if they were in love with killing). Whoever ended up with all of them won (They killed until it was empty and quiet). Adam walked and the moon followed him along the road (But not empty not quiet Then there was snow).

He let a crumb of sugar melt in his mouth (Silas with a fish on a string Look Ma) and remembered the turtles. There were two of them (Silas in his borrowed blue coat in town). She'd made a pair, with pebble eyes. He brought them in his pocket (When they returned to bury the bodies) to show them the river; the pebbles fell from the sockets (the soldiers stood by the pit leaning on their shovels) and he tripped on the bank and one slipped into the water (to pose for the photographer) and the current took it faster than he could run (with their clothes in order and their hats on).

He walked a long time, first whistling, then not (The snow) and the mosquitoes bit his arms and neck. He knew (covers the ground to protect) it was west of Salamanca so he walked that way (the food and medicine for another season) and ate all the maple sugar even though he wanted to save it (She taught him things when he was small); an owl screamed when he passed a farm (Sometimes when you’re afraid you can whistle) so his heart beat too fast to lie down (Silas asleep in his boots and his clothes). He kept walking until his boots hurt and he carried them (Did he think because he stopped talking she stopped listening) and when it got a little light (No) a man driving a wagon took a good long look at him (I am not so deaf I am not so faithless) and turned his head and drove on (I will keep by you wherever you go).

He slept when it was light and it took three days; near the end (In some of the creek bends there were islands) a Seneca man leading a mule let him ride (and she visited them In the day In the night). He hadn’t talked much and his voice sounded strange (taking off her shoes to wade in the shallows). Adam Jacket, he said. Turtle. Red House (and part the grasses to see if nests were there).

You're a ways from Red House, nephew. (All this told her)

I'm going to the penitentiary. (that she was not finished)

The man laughed. What'd you do? (that she was to stay)

My father works there. He's a guard (the fluttering). The man nodded. I'm bringing him a message from my mother (of the females’ blue shoulder notches when she disturbed them). The man had a piece of frybread wrapped around beans (the light on the males’ shining green heads); when he took it out of his pocket Adam's mouth filled with spit (the gray ducklings huddled and hiding). The man offered him a bite and he couldn’t stop eating it (then one afternoon three of them) and kept trying to say Sorry at the same time (between their parents swimming in a line).

That's all right, the man said, You go on ahead (If he’d had a club foot). I've got an apple when you're done (She thought of this along the road). Twice since leaving Salamanca Adam had stopped at houses (If he were deaf) and asked for food; once when the woman helping him (If she’d smashed the fingers of his right hand) went for water he took a piece of sausage from a plate (he’d be coming in from the field with his father), so he guessed he was a thief now too (and she’d be setting the plates of food down).

The man brought him to a fork and he walked the way he pointed (As she walked she left things by the side of the road) until he came to a big iron gate (a skirt she didn’t need anymore). He could see cows on a hill in the distance (horn combs her father gave her) and heard the sound of hammers against stone (her broad hat her wedding ring). When he saw the white man in the sentry booth he felt tired (a shawl a bible strands of her hair). My father's Hank Jacket sir, he said (She kept). Could I see him please.

The man looked at a list and then at Adam's feet (three old marbles that belonged to Silas) and back at the list. He was carrying his boots (a scrap of paper). Visiting time's four to five.

What time is it now please sir. (threaded with two of his rusty fishhooks)

The man took a watch from his pocket. Half past one. (her shoes because she needed to be walking)

Yessir. I'll just wait right here.

Can’t do that. No loitering on the premises. You'll have to clear out and come back (and the tin box) when it's time (of her grandmother’s seeds).

Adam walked a little way back down the road (What are you doing she asked) and sat behind a big maple and put on his boots and fell asleep (Why are you This has nothing to do with me). He dreamed about a boy falling through plates of ice (Why do you want me to stay here Isn’t it) as if they were shards of windowglass or mirror (enough now Isn’t it time to go home), how he slipped to where the ice was solid and lay there (and the sun would go down and the evening dampness) just under the surface with his face pressed against it (press against her skin and her clothes). People ran from the riverbank but so slowly (and the crickets and the first stars flickering), and the boy was saying something he tried to hear (the fire patterns all night crossing the sky) with his eyes but he couldn’t. He started awake (the willows hissing and silver) and the sun had slipped three fingers down the sky (and Lily Jacket coming up the road); he ran to the booth but there was a lady there ahead of him (with a baby in her arms Can’t I go home now) and she and the man talked for a while (The road held her and her home was there). When she'd finally gone he stepped forward (In the place they made for her by the fire). What time is it please sir (In the duck nests).