HOMELAND

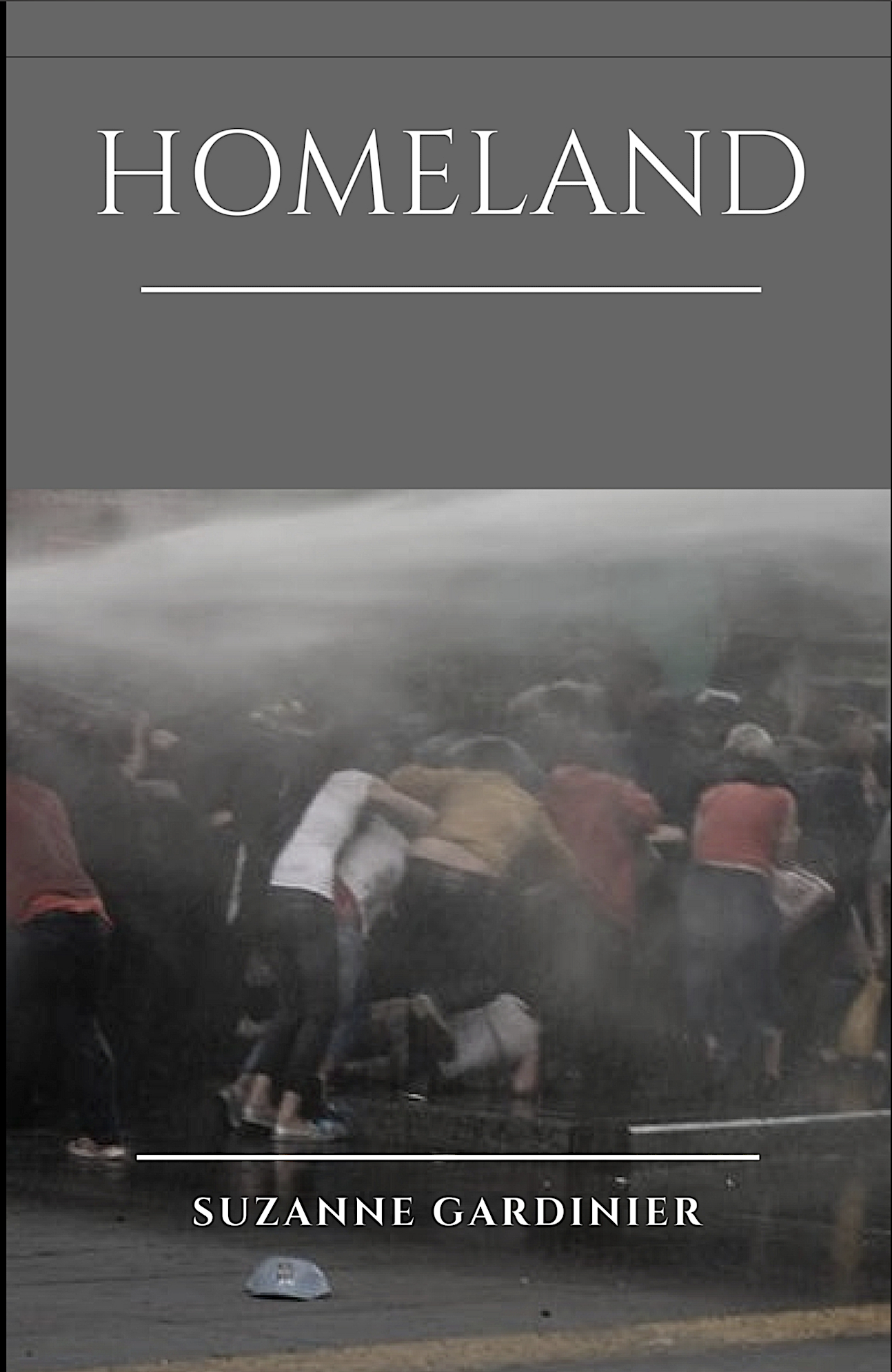

Homeland is a novel I finished in August of 2011; it's about fascism in Manhattan, people disappearing, and what a network of New Yorkers does and doesn't do about this. The book tells about twelve activists, who work for an international organization called the Crescent. It's dedicated to #Jan25 & #SidiBouzid, the hashtags for the Egyptian & Tunisian revolutions that were my introduction to Twitter at the end of 2010. I wrote the novel wondering whether those massive street demonstrations—say, on Wall Street maybe—could happen here. This is the beginning.

Rain

from Homeland

1.

When the tide turns, two boats set out, two rowers in dark jackets and baseball caps in the rain; when they get clear of the dock lights they pull beside each other, then apart, spreading a net between them. The white ball buoys make a line in the dark that drifts, then trembles, before one of the rowers has time to finish a cigarette. The river carries them and they keep their backs to the city, until one hauls in the net, laughing to see the four shad caught by their gills, gleaming in the oily light, and the other one hushes him and throws the end of another cigarette in the water and says they should head back. They tie up next to a bigger moored boat and carry a cooler between them; inside she tucks blonde hair behind her ears and looks out the plastic window as he cuts the filets with his big hands that make the knife look small, and broils them in butter and scrambles eggs, and she reminds him that when they were little and borrowed boats to catch flounder on hand-lines they’d wait an hour sometimes without a bite, and didn’t find out until much later that they were children toward the beginning of the time the sewage spills started to take the air from the water and the fish started to disappear.

Good thing I didn’t know how to filet then, he says. They used to put the flounder whole in the freezer and take them out months later to scare each other. Where’d you get that garlic? she asks, as the smell makes her mouth water. She hasn’t eaten since the previous night, in a room half an hour’s walk away, on a street where he was worried someone had seen him so he didn’t come up, so she ate a peanut butter sandwich and slept badly because she had no cigarettes, which he wouldn't have brought her anyway.

The greenmarket. We’ve got friends there. And dessert, he says, nodding toward his bag as he cracks the eggs; inside she finds a jar of raspberry jam. Look at you, he says to the flanks of fish as he settles them in the butter and garlic, and when he puts them on plastic plates beside the yellow circles of the eggs they look like children's drawings of islands in the sun. Laura’s by the laptop when he brings the plates over, too thin when he puts his hands briefly on her shoulders; Leave Tomorrow To Us! a woman’s voice is saying, over a logo of people locking arms in front of a flag. Tomorrow’s ours, motherfuckers, he says, holding up his plastic fork to toast against his sister’s, To Fish, she says, toasting him, My best brother-mama, and she smiles that way he loves and they eat.

2.

After midnight ten blocks away there’s an accident, one car swerving into the right side of another as they turn, blowing a front tire and crumpling the passenger door; the car that swerved pulls back and drives away, and the two people in the wreck run into the rain, so there’s nobody there by the time the HS car pulls up. Some of the people watching from windows remember a different city, where there would have been two drivers under umbrellas trading insurance information, and a police car passing and slowing down. Some of the watchers were born in that city, and some were born in other parts of the world, where the rehearsals were held to make this one, built over the other city that's gone now, and no one knows the new one's real name yet, or the ones who know can't tell. If I could tell you I would.

The two HS men walk around the wreck, talking into their earwires and to each other; then they walk across the avenue and take the man from Dhaka who runs the newsstand there. When the tow truck comes he’s walking between them with no coat, the rain soaking his blue shirt to his skinny chest and plastering down what's left of his hair, his wrists in white plastic and his head down, walking as if he's used to this somehow, as if it's something usual, as if he's done it before, in life or in a dream. They talk to each other but not to him, and they don’t let him lock his door, so by the time they’ve been gone fifteen minutes, three young men are taking cartons of cigarettes off the shelves. Rakib, Rakib, someone called him a long time ago, when his hair was dark and thick, to tell him they were taking someone else, in time for him to watch the young man he knew marched between two soldiers, handcuffed in the rain, in one of the cities far away in which the rehearsals were held.

The door of the building on the corner opens and a woman in a dark tailored raincoat steps out, under an umbrella, in shoes made for rooms and not for streets--It's Rita, she'd said a moment before on the phone, leaving a message to tell a story about where she was--and another woman a moment later, Kai, her name still sweet between them after Rita calling it upstairs, next to Jesus's, a little shorter in flat shoes and pants, with long locked hair tied back. They cross from slightly different directions, and stand on either side of the newsstand door; Kai goes inside, and in a minute the young men file out, while Rita stands at the curb, her back to the newsstand, at the bus stop, as if she's waiting. Kai turns off the light and pulls the grate, and they walk away in separate directions. By dawn it’s still raining on the broken glass in the middle of the intersection, and some of the watchers tell some of the people just awake that the women who locked up for Rakib after they took him had keys because they work for the Crescent.

3.

When Sami opens the café he notices the all-night newsstand's grate pulled; he's only seen it that way once before, for the three days after the attacks in September, and as then it makes him think of the street's face with one eye shut. When Gina the doctor comes in with her daughter, he calls the young woman Ghada, because he's known her since she was a little girl and her name is Grace, and that's how they say it in his part of the world. He spelled it for her once when she was in seventh grade, G H A D A, and she said Oh, like the Greater Hartford Auto Dealers Association!, and he shook his head and laughed, and said as he had before that it meant 'graceful girl.' He's old enough to be her grandfather, if everybody had married young. It also means lunch, he said, setting down her grilled cheese, And tomorrow, he said, Like this, pointing to the menu, where it says Café Next. Dr. Robinson, he says to her mother, who's hard to make smile but sometimes he can manage it, Can you do something about this rain please, as he hands her coffee to go; and because Kai sometimes comes at the same time, he adds another question she can't answer: Where's your friend?

Marco who works double shifts is a little late, and two tables of tourists are waiting for lattes and concierge advice by the time he arrives; Sami frowns as he runs in, and points with his chin toward the tables. The tourists have sneakers and a kind of genial blankness in the faces they turn up to give orders; Where are you from? they ask Marco when they hear his accent, and he tells them he was an electrical engineer in Buenos Aires, But too many people got electrocuted!, and he lets their faces sharpen before he adds Just kidding! and they laugh and turn away. They remind Marco of two young men he stood beside in Times Square the first night of the second war, or no, was it the third; there were too many now to keep track of, no one seemed to know the new one's real name yet, were there so many or were they all chapters of one. But he remembered that it was March, in the rain. The young men were drunk and imitating the voices of the people the police were putting in white plastic handcuffs and wagons, under the big screen of the president on the phone in front of a flag, the people yelling No as the new bombing started.

The young men stopped at the corner where Marco was watching the mounted police in helmets and rain capes pass under the big clock; Comunicado Numero 1, he was thinking, remembering the interrupted radio broadcast from when he was a little boy, the man's voice and a snare drum in the background, El país se encuentra bajo el control operacional de qué, de quién, The country under the operational control of what, of who, he couldn't remember, but something about that night reminded him. When the long hand got to the twelve, the two young men cheered, then changed to whistling when a woman in tight jeans walked by. They smelled like beer and that strange American combination of bubble gum and cologne, like children with five o'clock shadows, their faces like newly printed magazines with nothing on the pages. You got a girlfriend, man? one of them asked, and he didn't answer, and they repeated it more slowly and loudly into his face, the face that seemed white at home and brown here, What's her name? Angela, one said, pointing to his own chest, Beth, pointing to his friend. You?

A wife, Marco said, just as the light changed. Lina. She's where those bombs you like are falling. When the tourists' cups and plates are empty he leans in, and they don't look up when he says smiling, Let me take these, so you don't have to keep seeing everything disappeared.

When Rose comes in it's slowly, with her joke about how long a mile is for someone old, and she takes off a wet scarf, and her wet dog settles under the table by the window; when Sami brings her coffee they look out at the grated newsstand together, as the sweeper swerves out to the middle of the intersection for the broken glass, then back to the curb. She knew his parents from meetings in the neighborhood; she'd given his mother a job in her lab when they first came, and when he was older they laughed that she'd come from Vienna fleeing the Nazis in 1938 and he'd come from Beirut fleeing the Israelis in 1983. Look, we're twins, she said, and told him she didn't know any word in English for brother-and-sisterhood at the same time. Ummah, he told her, laughing a little at what his grandmother would say. Her dog was a rescued mutt named Tarvisio, for the town in the Italian Alps that let them go. She called him Tar, one of Grace's first words. When Grace was a little older they'd sit by the window and talk about the world; Sometimes you just need that little guy with a gun, Grace would say, twisting a braid with a bead at the end of it, and Rose would shake her head and look out at the street. What about behind him, she'd say, and Grace would say All right, two little guys with guns, and when she was older, What about revolutionary war?, and Rose would look at her and ask, Do you know what an oxymoron is? She and Sami look at the newsstand grate, and she says, In Vienna before we knew what was going on, when we'd see that in the morning, we'd say Well, he must have done something.

When Rita stops for tea on her way downtown, her hair's still damp from her second shower, the first toward half past one in the morning, after she'd said hello to the night doorman, folding her umbrella, and read Nick's text on the elevator--Hey sorry tied up downtown home by midnight promise--and found him in front of the television asleep. She'd showered while he slept as she often did, so she wouldn't smell like someone else.

Under the sheen of the water she could see the faint summer line from her bathing suit, and thought of the meeting she'd chaired the previous morning, how the antagonists took their usual positions and she tried to stay in the narrow place between them, one foot on each side, and see who she could get to cross. On the paleness of her left breast is another line, curved, just above the nipple: the arc of Kai's teeth. After washing she puts on a slip and stands behind Nick's chair to touch him and wake him, and when he settles beside her it's with his hand on her hip as usual, as if her body were part of his, and his smell is the last of the world's messages she opens before she falls asleep.

On the way to the Next she passes Jimmy who lives around the corner, and notices that he's the only one of the three of them who hasn't started to dye his hair. They've known each other since they used to skip their City sociology classes to go to demonstrations, or to smoke a joint in his room and introduce themselves to the mysteries of heterosexuality, listening to someone's sister's sitar music or You Can't Always Get What You Want, and sometimes answer the phone and sometimes not when Nick would call after class, before the Brooklyn diner shift he worked because his father didn't have a job anymore, to say Where the fuck were you guys.

She sees Jimmy on the corner in his open raincoat, and when they're near enough she lowers her umbrella to stand under his; Morning, professor, he says, How's our capitalist?, after kissing her cheek. Okay, Same, Busy, she tells him, and notices how nobody asks How are you? on the street anymore. Tell him he owes me a day at the track, Jimmy says. Tell him I'm in need of a skilled gambler.

Good luck with that. He's not big on days off.

I'll flash my badge, Jimmy says laughing. On his lapel is a little circle pin divided in three. He's on a board at the transitworkers' union.

You got a permit for that? she asks. She's worrying about the time but she doesn't want to go.

Hey, we move New York, honey, don't you forget it. She looks at her watch.

Gotta go. Nice to see you. I'll tell Nick, she says, and steps back out under her own umbrella.

Tell his wife she owes me dinner sometime.

Will do, she says, smiling, but by the time Sami hands her the hot cup in its cardboard sleeve she's forgotten; she's thinking about the girl in her immigration seminar who never says anything and how she made her laugh last time, but she can't remember what she said, and worrying about the time and about Kai, who should have texted by now. 'Earl Grey with milk,' Sami thinks when he sees her, and 'Peanut butter tartine,' because that was the American cuisine he prepared to celebrate getting his green card with the help of the lawyer she put him in touch with, and 'Wife of the Wall Street guy,' whose name he rarely remembers, and 'Kai's new friend.'

Kai gets to rehearsals by nine, even though they don't start until ten, because the meister is never late; he has a way of holding up his hands for silence as any latecomer crosses the stage, a walk she walked once, the only brown woman, and startled awake from auction dreams for a month after. She's sleepy, so before she has her tea she runs up the hall stairs and back down; the woman from the islands who works the concession has seen her do this and laughs, and when they sit across from each other Kai asks about her children. When she took the train downtown early that morning the stairs were light, so she hardly noticed them, changed to different stairs when she was tired on the way home. Before that she'd walked up Sami's stairs, because his elevator was slow, and knocked on the side door by the garbage cans where he slept his jittery sleep on the other side, and he handed her the envelope he fetched from his file in pajama bottoms with his hair sticking up. She left it in the screen door crevice at Max's downtown, for Laura's brother Fish whom she'd seen once by mistake, a big man in a dark jacket and baseball cap, but might not recognize again: the screen door to the kitchen where the dishwashers stood to smoke, just a few clangings and voices from inside by the time she got there, the door locked, but the screen door free as usual and the little cleft between the mesh and the wood, Fish's mailbox, where she put the photograph Sami had taken with his cellphone not long after the man from Dhaka opened the newsstand, and a note with his name. Rakib Ahmed. The tea's too hot and it burns her tongue and she's grateful to be getting ready to play with her hands and not her mouth. Just before she turns off her cell she sends Rita a text: Angel. Smooth sailing.

There's a message back but she won't see it until after rehearsal, when she's heading downtown again for another trip to a different mailbox, and remembers to turn on her phone; she reads it once just before the subway stairs and it turns her fatigue into something else, and when the phone's dead underground she keeps reading the message in her mind, and hearing the words in Rita's voice. She walks to a little alcove next to a gallery, crowded with posters and graffiti paint; she's hurrying, the light's getting small already and she has to get to Gina's and not be late to play that night. She scans the alcove for Fish's new post: blue paint to indicate the prison in Elizabeth, red for Queens, black for 201 Varick and white if someone's gone. One dot below means solitary, circled like a period so no mistaking. Three dots above in a pyramid means Enhanced Interrogation, like over the Arabic letter that says Shh. It's almost at street level this time, he must have been sitting when he wrote it: Rakib, in leftleaning flourish letters. In black. With three black dots above. And a circled dot below, and a number: he's on the fourth floor. She whispers it all to herself like something she has to play, so she can carry it to Gina without writing it down. As she falls asleep later she sees it again, written in Fish's paint along the cello line she plays in the Matthew Passion, as if it were a path she could walk, one that stops just after the alto keeps singing Wo, Wo, Where--then there's silence, which is either desolation because she can't translate or the most beautiful music she's ever heard. In the dream she can't decide.

Gina's sitting by the window across the street, the information Kai gave her sifting through her body like some painkiller turned inside out, instead of bringing peace taking it away. She'd taken the little photo out of her double of Sami's file and scanned it, and Kai stood at her shoulder while she typed the rest into the computer for the flyer. Rakib Ahmed. In the photo he looks out of the frame to the side, as if he's already started the work he's going to do when Sami finishes taking his picture. March 21. Disappeared. In smaller print below, she put where they've taken him, and what they're doing to him, Fish’s news from the day's rounds passed on, and the little crescent from some website that follows the phases of the moon. She printed twenty and erased the file. When she looks down at the street shining black in the rain, she can see her daughter Grace standing at the bus stop, with the boy down the hall she's known since they were babies, Rose's grandson--Take Aaron to watch for you, Gina told her, and gave her two pairs of exam gloves--and under her baggy rain jacket the brush and the squirt bottle filled with the mixture of flour and water that makes the posters hard for HS to take down. As Gina watches they walk laughing, they've practiced this, how to look like two American teenagers who don't understand anything, and watches as they duck under a strip of scaffolding with a stretch of dry wall.

She turns on the radio, as Sami turns on his around the corner, and Rita scrambling two eggs because she didn't have dinner, and Marco emailing Lina that fast note-to-note way that lets them pretend better that they're in the same room; Fish is scanning through the radio on his phone from a tunnel by the river, and he doesn't find the frequency until he hears his sister's voice. Gina's in time to hear the music of Plantation Lullabies, Laura opens with this, and everyone else in time for the recorded applause that comes next, and the piano, and drums but not like the ones Marco remembers, and then a familiar woman clearing her throat, to sing about the words you can't say, from Carnegie Hall in 1956, just before a midnight she can't sit in the front seat of a bus in Montgomery, and three days later the Supreme Court says she can. You'll get bold, she sings, with a clarinet playing quick and sweet over her shoulder, the tempo clipping but she's wise and in no hurry, You can't resist him, and waves of clapping and whistling when she's done, just before she makes a happy sound in the high part of her voice and laughs a little, as if it surprises her too, What a little moonlight can do.

Someone else starts the mix of recorded introductions: Distinguished guests, he says, his familiar voice oak, where hers is honeysuckle over a burned place, Brothers and sisters, he's a believer and she's not so sure, Ladies and gentlemen, Friends and enemies, and then It's midnight, and live: This is Laura Keys for Plantation Radio, she says, Fish's sister, her antenna wire floating out the window of a room he found for her. He picks her up when he hugs her. He’s Fish because that's how she said Christopher when he was born. Once when they were drunk teenagers in Falmouth she dared him and he had a cod tattooed on the palm of his hand. He cooks for her and brings her a jar of jam, so he's bringing raspberries in winter, along with the sound files and the stories for her to echo out and hope for an answer. Twelve people last night, Laura is saying. Mohammed Shah, Elizabeth. Jamal Bakar, Elizabeth. Rachel Wolf, 201 Varick. Five hundred dollars a week passed from Nick's gambles to Rita to Kai to one of Fish's mailboxes pays the mechanic for the guy in the southwest sentry booth by the loading docks, so he can keep running his car between his day job and his night job, and then he tells Fish what time they show up and what floor. Fish brings him soup too. Cecil Bates, 201 Varick, Laura's saying. Rakib Ahmed, 201 Varick. Eqbal Dajani, Disappeared.

Before the end she plays a Porteños song they won't play on commercial radio anymore, a reggae groove but a muezzin voice way in the background, a guitar line snaking through like a fire along a fuse, and Grace appearing in the doorway with her jacket wet and no leaflets makes the air come back into her mother's lungs. Turn it up, Ma, she says. The young man's voice sounds like he's been awake all night; Step up, he says, We got a big sale on fear. All you want, no questions asked. Where's what you promised, says the customer--Grace is singing along as she takes off her wet clothes in the bathroom--Putting on a courage mask. Laura knows where she'll sleep this night but not the next. This is Laura Keys for Plantation Radio, she repeats, to sign off. Who's missing?

4.

Before sleep Kai pours a little oil in the skillet, and the smell of the tortilla is a message she thinks her grandmother would have understood, a message that would have let her stand beside the corn; she folds two in half hot and smears them with goat cheese from the Pyrénées, it says this on the package, a red and white leaf of radicchio forced in the dark near Venice, where she’s played more than once, a cucumber from south of the border but she can’t remember, and a cup of tea, from Ireland and maybe before that from outside Mombasa where she played once, or outside Dhaka, where Mr. Ahmed is from, where she played and where someone she knows still lives.

It’s the end of winter, crossing into spring; she’s wearing the soft pants she sleeps in when she’s alone, and the concert shirt still, unbuttoned, the coat on the hook streaked with rain. She leaves the kitchen light on and eats in the other part of the studio in the dark, then washes her hands and sits in the chair by the window and takes her cello in her arms. You’d think I’d be tired of you, honey, she says, but there’s a cradle song she can’t get out of her mind, and she needs help to put it to rest, at least enough rest to sleep tonight, into her body and out into the night the humming of the Paris maple her cello used to be, down to the street where she can see the cardboard spread under the sheltered part of the bank steps, where a man whose face she knows sleeps when it rains.

Is this the way to find you, habibti, a word Lina taught her in the café, what Lina said when Grace was a little girl; Kai’s thinking of the photograph in an open window on her laptop, hidden behind others for days, did Lina send it?, she can’t remember, a girl in sleeping clothes, she remembers that, from the brief glance before she had to look away.

The cradle song moves like the winter wind through the streets by the river, but the pattern sweet, until she can stand and cross the room to the laptop and look, at the girl’s face and the faces of her cousins; Dear Kai, Lina last wrote, Having a wonderful time, Wish you were here. Many adventures with the cowboys. Give that red girl a kiss for me.

In the photograph, the girl’s left shoulder is hiked up, her cheek against it, dark eyes half open the way Grace’s used to in deep sleep, is she seven? eight?, wisps of dark hair on her forehead and temple, lips open as if she’s about to say something. Whose list were you on, baby, Kai wonders, sitting by the window again, Did you know you were in someone’s experiment, when something happened on the way to the morning--and then she can see them, standing between the notes of the cradle song, the armored men boarding a plane in a place whose languages they don’t speak or understand, landing two kilometers away from a village and walking toward it in a line.

As if she’s about to say something, but interrupted--and a little necklace, a blanket behind her head, and the fringes of another over her right arm, where someone tried to keep her warm, a soft jacket there, but on the left it’s gone. The blankets are spread on a woven straw mat on dirt, and the sun’s finding all of it, finding what happened in the night, the way the survivors will tell the story: On the way to the morning something happened, the Americans came.

The announcers said a training camp and three hundred fighters, they didn’t mention you and your cousins; ‘foster development,’ they said, to try to make sure your uncles aren’t so poor they try to send the message of murder back again, ‘international cooperation,’ looking for what the last centuries of international cooperation didn’t take, by sending you a line of armored men and a plane with no one inside it. The father of your death has a daughter your age, he must know your face: your lips open as if you’re about to say something, but interrupted, and lines of blood along your jaw and cheek, as if blown back by a wind, or was it forward, as Kai leans into the sweetest part of the music and closes her eyes and breathes, Because in the dappled sun on the blanket behind your head, parts of your brain are tangled in your hair.

Your cousins are mostly babies, some of the wrapped bundles on the dirt floor open, smoked, visible inside, split from throat to thigh, one older boy with the bloodsoaked waistband of his poorboy trousers slipping down his skinny hips, his arm bent up as if he’s waving--only a couple of weeks since they were absorbed in their beginnings, looking for what they might need to be a woman and a man in this world, until the men who stopped at the edge of the village and the plane with no one in it, after someone on the ground said Roger that, because higher approval isn’t required if twenty-nine or fewer of you disappear. Kai rocks with her red girl, back and forth, eyes closed, playing, remaking all the prayers she knows: Our children who art wasted, Hallowed be thy names. Blessed are you, who kept us in life, who performed miracles, in the days you lived. There is no God but you, and these messages passing back and forth over the gulf between us.

________________________

Last night just now you were kissing me; we were sitting with our knees touching, your raincoat across yours, because we’d dressed and you should’ve been gone, someone was expecting you. You were kissing me in the dark, holding my face, my right hand on your knee behaving, my left at the back of your neck; in the streetlight I could see the lines at the edges of your eyes that get like that when you’re worrying about the time, and under the buttons of your shirt a warm animal not ashamed or worrying. I know, I’ve seen her. The animals are dying, but not here.

On my knees between yours I rub my cheeks against your nipples through your shirt, back and forth, remembering in the streetlight the bit of rose and the bit of dirt in the color, remembering when I was your famished son, telling the story of when you wouldn’t welcome me, of when I knocked and you wouldn’t answer because you were afraid. Your softness is hidden again, banned in the proclamations, did you read them?, and you take my hand and press my first two fingers back inside, after I’d undone the button and pulled down the zipper to remember, interrupting the story I was telling, of the twins who are adversaries, who pretend not to recognize each other, who are keeping a secret. You wrap your fingers in my hair and say my name but they won’t tell. As I move my hand in you you’re telling another story, although you’d prefer not to; you’d prefer at this moment to be someone coming home late from work, hidden under an umbrella, a woman in her fifties who says hello to the night doorman, looking up from reading a text from her husband, who works downtown. But we’re making each other, so as I fuck you slow and deep as I’ve been doing for hours you tell me about the waiter at Max’s two days before and the hair on his chest, the line of his hip and the message: Don’t tell me, I say, You haven’t told me all night, Don’t tell me, then I’ll know. The message was an address, your voice stripped of every hesitation, soaking my clothes, 67 Chambers Street, one of the hiding places, and you’re telling me how he fucked you standing up in a little alcove off the kitchen, while you whispered to him about his mama; Don’t, he said, but in his face a kind of melting, his young eyes and the cut of his mouth beginning to dissolve. You tell me the address as I fuck you because you have to tell me everything then, that’s what wet is for, bringing solvent ruin to marriage contracts and family picnics and holiday parades, and you keep talking, about how he left first and you saw the HS men come from two different directions and take him. And when the sound of metal and broken glass interrupts from the street, when I’m fucking you and kissing you and rubbing you with my other hand, the worry flickers across your face but you hold my wrists to keep me from stopping to look out the window and you whisper, Finish me.